|

OLD SORREL—A condensation of a

monograph by his great grandson, Rev. Robert E. Walker.

By Orrin Manifold

Source: NMHS Newsletter, Nov 1986

Old Sorrel is the 1985 account of

Gilbert Moore, a Chester Township farmer and American

Civil War soldier. At the age of 43, father of eleven

children, he enlisted in the Union Army, fought in

Tennessee, was captured, and died in Andersonville

Prison. The account was researched and written by his

great grandson, Rev. Robert E. Walker. Moore was known

as “Old Sorrel” because of his red hair.

Born in Rush County and married

there in 1842, he and his wife, Delilah, and several

other families moved the next year to Wabash County near

Treaty, and then in 1856 he purchased an 80 acre farm in

Chester Township.

After the Civil War broke out the

Moores’ oldest son, John, enrolled in Company D, 47th

Indiana Volunteers of Infantry. Two of his brothers

would also serve in Company D. In August, 1862, Gilbert

Moore enrolled in Company F, 101st Regiment

of Infantry Indiana Volunteers. He was probably

recruited by Captain Benjamin Williams of Wabash. In

those days a well known man could enlist men and be

elected by them as an officer. The regiment met August

16 in Wabash for organization, speech making, and flag

waving. Joseph, age 18, and Jacob, 16, were old enough

to carry on the farm work.

On September 2 the regiment boarded

the train in Wabash in high spirits. At Noblesville late

in the evening local people fed them chickens and

turkeys, cakes and pies, melons and good coffee. They

were officially mustered into the army September 5 at

Camp Morton in Indianapolis, and each man received a

uniform, a blanket, gun, haversack, and canteen. He had

to furnish his own cup, plate, knife, fork, spoon, and

skillet.

Two days later they left by train

for Covington, Kentucky, to protect Cincinnati, which

was being threatened by Rebel General Kirby Smith. When

he did not come, the regiment boarded a steamer on the

Ohio River and sailed to Louisville, Kentucky. While in

Kentucky for the next several weeks, they found an

occasion to visit Mammoth Cave. They engaged in action

against “Morgan the Raider,” discouraging him from a

Christmas raid into southern Indiana and Ohio. Two days later they left by train

for Covington, Kentucky, to protect Cincinnati, which

was being threatened by Rebel General Kirby Smith. When

he did not come, the regiment boarded a steamer on the

Ohio River and sailed to Louisville, Kentucky. While in

Kentucky for the next several weeks, they found an

occasion to visit Mammoth Cave. They engaged in action

against “Morgan the Raider,” discouraging him from a

Christmas raid into southern Indiana and Ohio.

In the next months there was brisk

action in central Tennessee against General Morgan and a

concerted campaign in late June to drive the Rebels out

of central Tennessee. The northern troops pushed on

towards Chattanooga, where control of the railroads

there was the key to the whole area. Heavy rains over a

considerable period of time made nasty weather. Often

the men had to wade rivers and creeks that had

overflowed their banks. Several men died in the

hospitals around Murfreesboro.

Confederate General Braxton Bragg,

commander at Chattanooga, decided to make a stand along

Chickamauga Creek, a few miles from Chattanooga. The

battle continued for two days. The night between was

cold, but there could be no fires which would reveal

their locations to the enemy. In the outcome of the two

day battle the northern forces were defeated; but

General Bragg did not follow up on his victory, so the

Union Army claimed Chattanooga and held control of

communications and transportation. This made possible

the capture of Atlanta a year later and Sherman’s March

to the sea.

On the first of the two days the

101st from Indiana plunged into the battle

about noon. About 2:30 p.m. Confederate General

Alexander Stewart made an attack which pushed the Union

army back in this section. Lt. Richard Busick was

wounded and an officer ordered Corporal Gilbert Moore to

stay with him. When the Union Army pulled back, Moore

“refused to leave the lieutenant and was taken prisoner

by the Rebels”—as was also lt. Busick.

From the battlefield he was sent to

a prison in Richmond--probably by way of Atlanta and

Augusta, since the Union forces controlled any direct

route. He arrived there September 29. It is not known in

which of the five prisons he was confined. Most of the

prisons there were brick tobacco warehouses, two or

three stories high. In October General Robert E. Lee

suggested that there were too many prisoners in

Richmond, so six brick or wooden tobacco factories in

Danville, Virginia, were hastily readied to receive

prisoners. Gilbert Moore and William Busick were sent to

one of these Danville prisons December 12, 1863. That

day a smallpox epidemic swept through the city.

At some later time—perhaps in early

march, 1864—Moore and Busick were transferred to the

Andersonville, Georgia, prison. A double stockade of

twenty foot pine longs enclosed 26 ½ acres. Stockade

Creek—about five feet across and a foot deep—was used

for bathing, cooking, drinking, washing clothes, and

flushing out the sinks. As the war continued and the

prison population grew larger, the food deteriorated. In

all, 12,912 men who were imprisoned there died and were

buried in the cemetery. Disease was common—particularly

scurvy, diarrhea, gangrene, and dysentery.

Scurvy makes one’s extremities

swell to twice their size and the patient’s teeth often

become loosed and fall out. It is reported of Gilbert

Moore that “three hours before his death he pulled out

his teeth, then checked into the Prison Hospital where

he died that same day,” probably September 4, 1864, two

days after Atlanta surrendered to General Sherman.

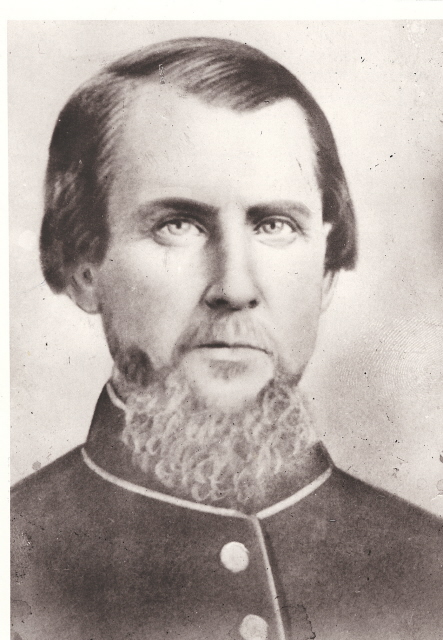

Note: The above photograph

of "Old Sorrel" in Civil War uniform is from the collection of Nancy J. Reed.

Gilbert Moore was Nancy's ggggrandfather.

|